AB: After you came back from Dachau, you had to go to--

EF: --I had to leave immediately.

AB: Did you stay in contact with your family? From Holland--

EF: --yes, from Belgium.

AB: How did you do it? With--

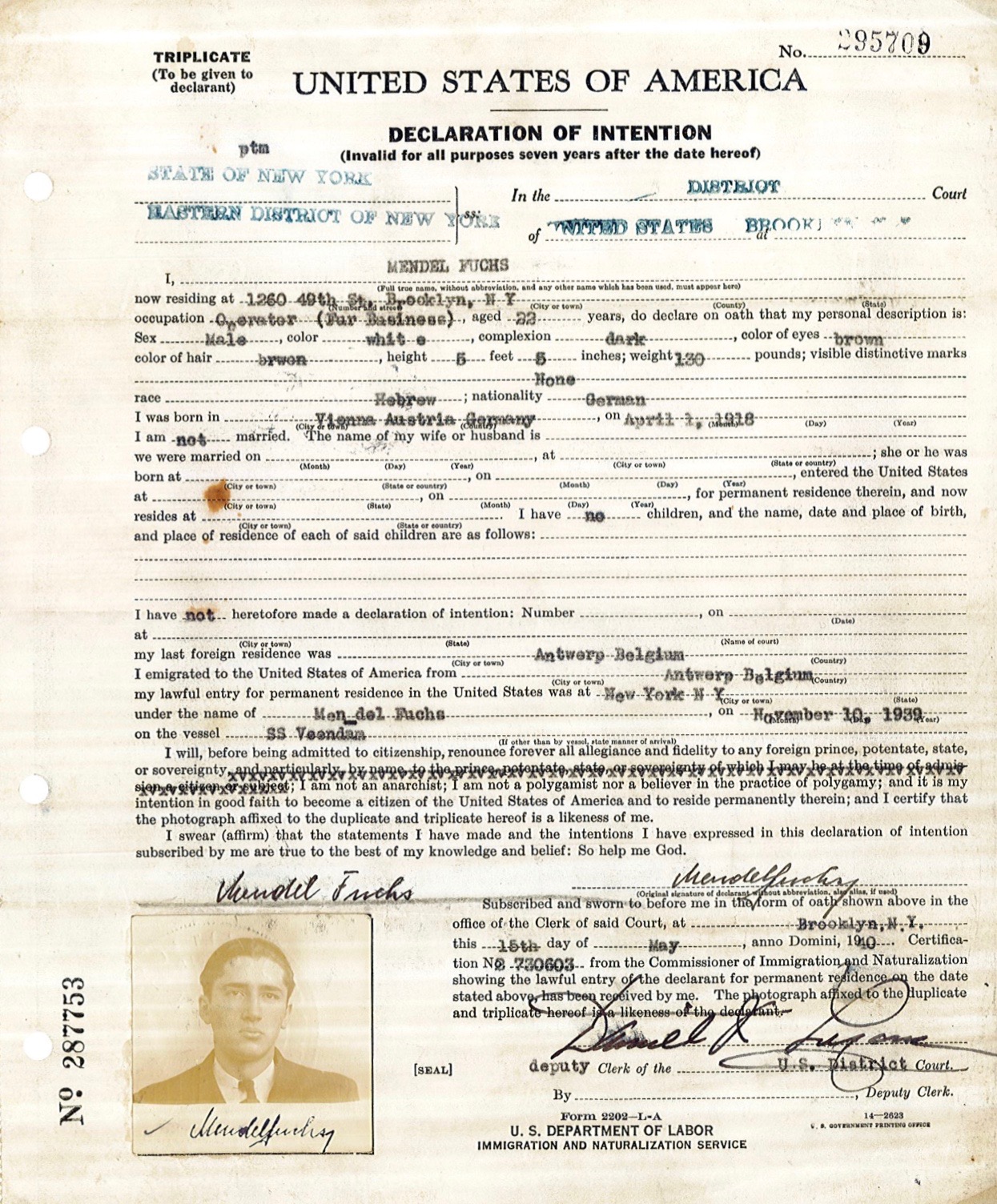

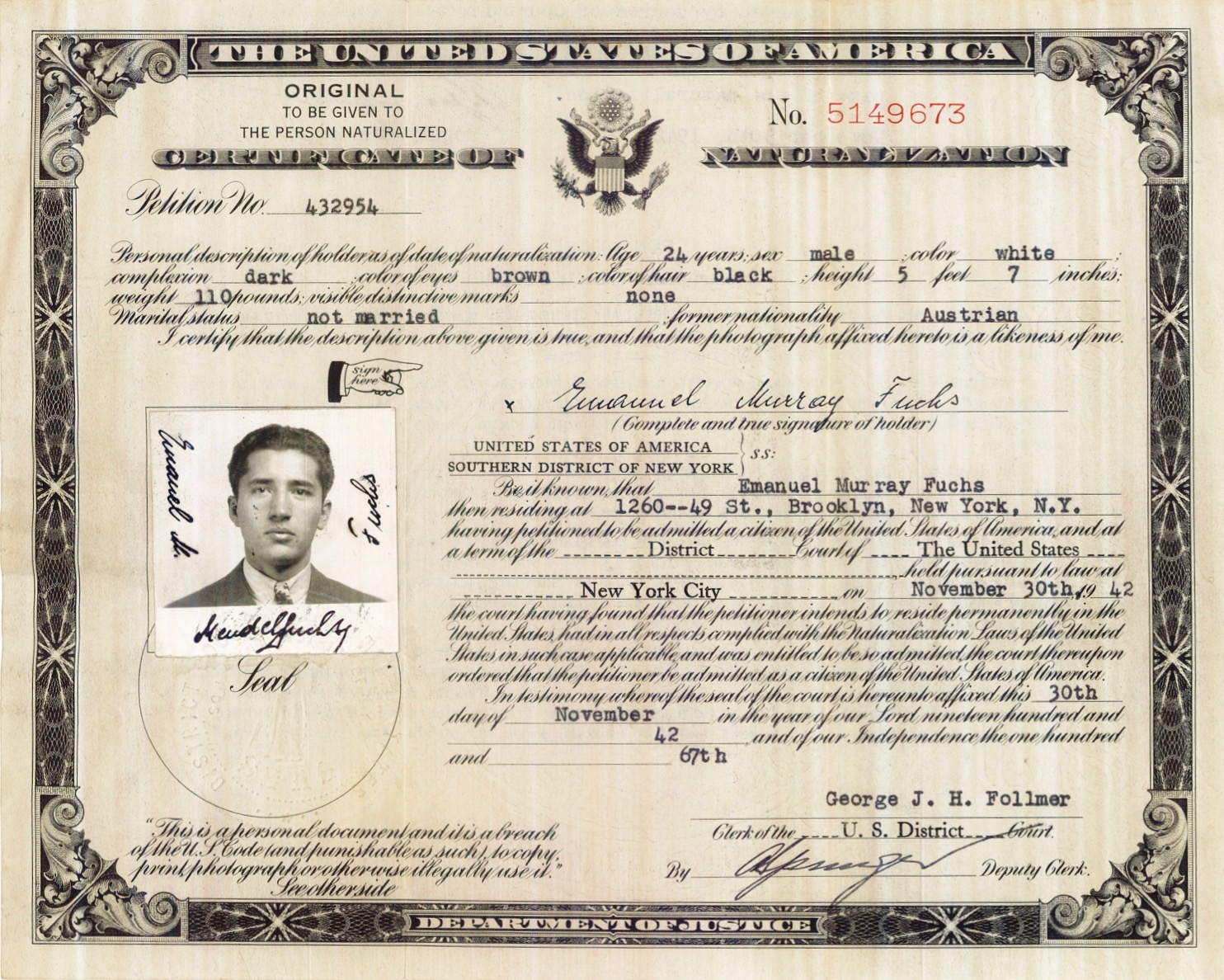

EF: --mail. Yes, there was regular…there was peace, still. This was at the end of [19]39 and [19]40…no…the end of [19]38! The Kristallnacht was [19]38 and in the beginning of [19]39…until September 1st [19]39, when they bombed Warsaw, it was peace and there was mail – and I corresponded. And my parents were still living there, where they were, and they remained there until I came here to America. They couldn’t go anywhere. Everybody went somewhere…eight children…everybody went, only my parents stayed. I couldn’t help to stay in touch with them from the army here until 1941, from America. – There was still way…through the chaplain that I was able to send mail to Austria. In 1941, which was after we already had war…America was at war with Germany. I don’t know how, this may been through the pouch, army mail or whatever. – And I stayed in touch with them until June or July [19]41, when a letter came back. And as I found out now from this…on this…what it says here. [Nimmt einen Zettel.]

AB: The letter from the DÖW [Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes]?

EF: Yes, they have a deportation transport number…to the ghetto on November 2nd. They have the date exactly: November 2nd.

AB: So, you found it out only two years ago.

EF: No!

AB: Oh, you told me: only two months ago.

EF: This year, two months ago! I spend hours in Israel, they have a film…you can look through…what they call that micro--?

AB: --microfilm.

EF: Yes, microfilm. And you look through every Lager…I looked through to find tracesaAnd I couldn’t find them. I was in Vienna bei der [Israelitischen] Kultusgemeinde and they couldn’t find them…I couldn’t find them. I went…sent to the Staatsarchive. – nd the Austrians are so exact with the archives, everything is archived. They found out I was in Dachau – they know exactly when. They told me they know exactly when I was there and how long…to the day, but they couldn’t find out what they found out here. That they were transported from Vienna and that there was a mass transport that took place…“5.000 Jewish victims from Vienna arrived in large between October 16th and November 4th, 1941.” And they couldn’t find out what happened.

2/00:26:01

AB: So, only the DÖW was able to show you--

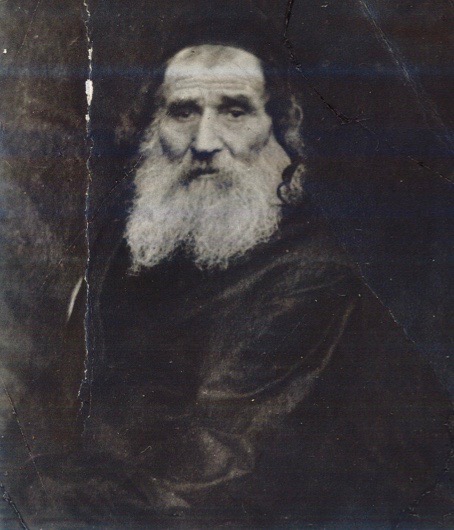

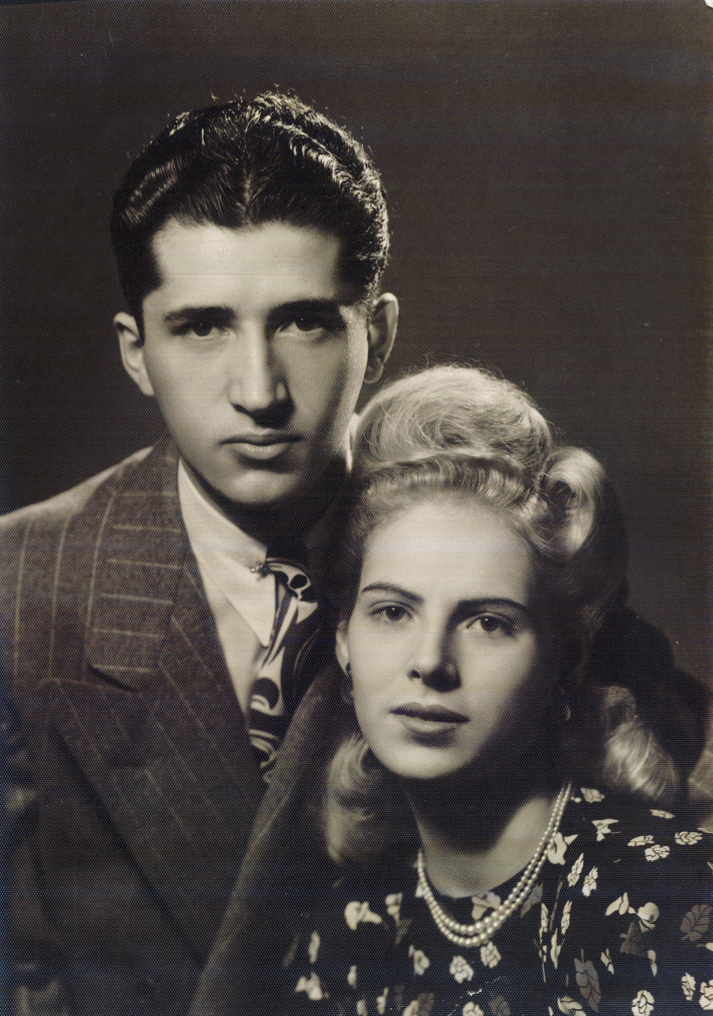

EF: --they found out. Now, don’t tell me that knowing Austrian order, they did not have documentation of that transport when the Germans ordered that transport. How it came about…what happened – nobody knows. There is nobody that…there is no record. Somebody destroyed these records just like the records on my father’s factory disappeared. Somebody walked in there and took it. There were big machines. My father saved his whole life and paid off these machines. There were machines as big as this…you know in those days you used to cut books by hand. When you had to cut a thick book like this…Hebrew books, this thick – you had to cut it. So, there was a machine that was that big, that developed power where you cut. And there was a press that was just as big, where you pressed covers. And the covers…he bound very expensive books, certain very exclusive books that they read in certain higher learning of Hebrew. And no trace…and no one found out who took over the apartment, who took over the factory – there is no record. Now the building stands there, I am sure. Because my building is there – I was there. I saw there is a flat there. The building was bombed by the Americans, I think. And my daughter wanted to see it. We went up to where I lived. But there is no trace, no one could find out what happened. So, they gave us now a…final pay-off of 7.000 dollars. Now that does not…that reminds me of an incident: My wife was born in Berlin. And we met here, and she was young and she left Berlin, she was twelve years old. Yet the Germans found it important enough to invite her and me as her husband. And we went to Germany on a trip. They took us there and they were very nice, very hospital both, they showed us around. That was a time when it was a divided Germany. They chauffeured us, they gave us tickets to the opera, they treated us as guests. So, I wrote to the Austrians and wrote, “Don’t you think you owe me at least to…do the same that the Germans do? My wife was in a concentration camp. I paid for it.” So, at first they wrote, that they cannot do anything.

Then maybe five years later, they invited me. And I kept that because this is something I will never forget. [Holt den Brief hervor.] And I didn’t really…I have it here. This is interesting: They invited me to come to Germany. Now, the invitation is the kind of invitation that is not very friendly, let’s put it this way. The invitation reads very clearly. There is a paragraph, “Sollte es Ihnen, aus welchen Gründen auch immer, nicht möglich sein, diesen Termin wahr zu halten, gibt es dafür keinen Ersatz und ihre Vormerkung bzw. Einladung erlischt. Leider sind wir zu einer solchen Maßnahme aufgrund der vielen Wartenden veranlasst.” Das war…das Datum…what was left was very few…I don’t remember the year…[19]99. Now there were in [19]99 from…[19]38, that’s what? 33 years…imagine how many are not here anymore, how many are left…percentagewise…to send me this kind of invitation. So, I would like to put this on record, if they like it or not and whether it is worthwhile or not: I resented the fact that they sent me an invitation where they told me very clearly, “Für eine etwaige Begleitperson bezahlen wir die Transferkosten und Veranlassung der Buchung für das Hotelzimmer.” That means that they let her sleep with me, “Für die Bezahlung vom Flugticket und das Hotelzimmer muss diese begleitende Person ausnahmslos, auch wenn es sich um ein Ehepaar handelt, selbst aufkommen.”

2/00:30:53

Now that was in 1999. I wrote them back – I tell you the truth, I was very upset – and I wrote back, “First I would like to thank you for the invitation to visit Vienna. As a former Austrian citizen, born and raised in Vienna, I have some thoughts, which may be of some interest to you: I was born on April 1918 enjoying life in a free environment until the sudden end in March 1938. I was deprived of a normal life in the city of my birth on the Crystal night, November 10th, 1938. As a Jew I was deported to the Nazis by a school college and sent to Dachau. On December 1938, after being released from Dachau, I had to flee Austria at night into temporary asylum in Belgium, where in December [19]39 I was finally able to emigrate to America and establish a permanent home. I left my parents in Vienna never to see them again, since they were sent east and were never heard from again. In the invitation to visit Vienna you attached very stringent conditions. I must assume that the purpose of this invitation is…someone’s intention for me and others invited to, somehow, renew our feelings for our former home. As much as I appreciate the good idea, I wonder whoever is in charge of the program really has an understanding and sympathy for the person invited. It was 1939 and I was twenty years old when I left my home in Wien. 60 years have gone by, when today I receive this invitation to come for a visit. I am now 81 years old, married for 55 years and I am told in very stern words, ‘Come alone, we can’t afford to finance your wife’s transportation and hotel.’ I cannot understand this insensitivity to my feelings. Do you think I would leave my companion of 50 years…56 years at home because I am financially unable to meet the cost? What is the motivation behind this offer? If this is a matter of economics, how many people are still alive and able to use this invitation? I believe this is supposed to be a friendly gesture on the part of the Austrian authorities. At this time, 60 years after the Anschluss, when surely not many former Wiener are still alive, this offer should be a little more understanding and generous. I believe with the attitude demonstrated in this offer, the message conveyed is not of genuine feeling of welcomes. Sincerely, Emanuel Fuchs.” – I never received a response. It means nothing, but I felt better. I had to get that of my chest, because I believe it tells something about people today – this is in 1999 –, how people feel in 1999, 60 years later.